This is part of a series!

Part 1 (Work) Part 2 (energy bar charts) Part 4 (Vertical Whiteboard +Lab)

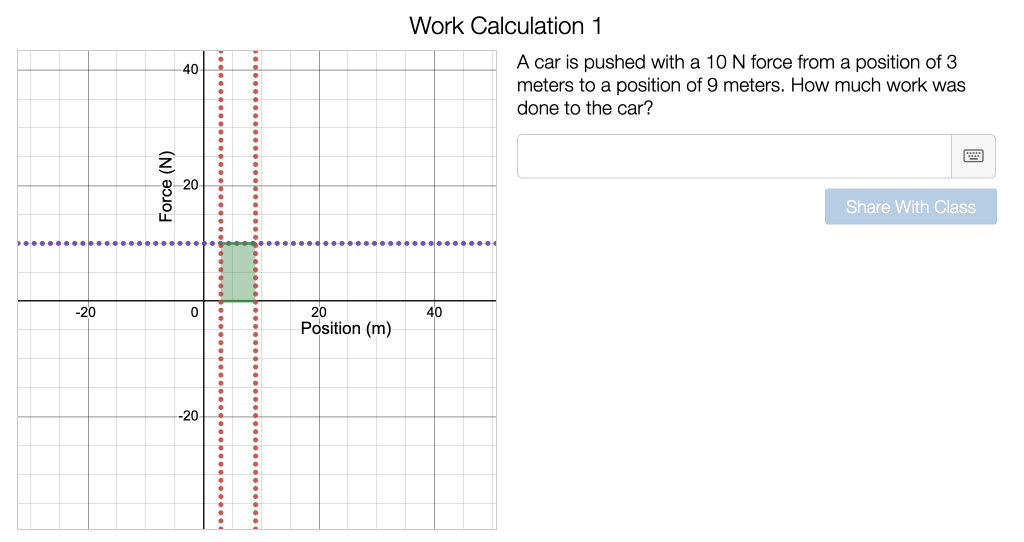

After over a week of work and various representations and practicing energy bar charts we finally dive into the math. We’ve already created mathematical models for spring energy and gravitational potential energy and I give them kinetic. Now we begin.

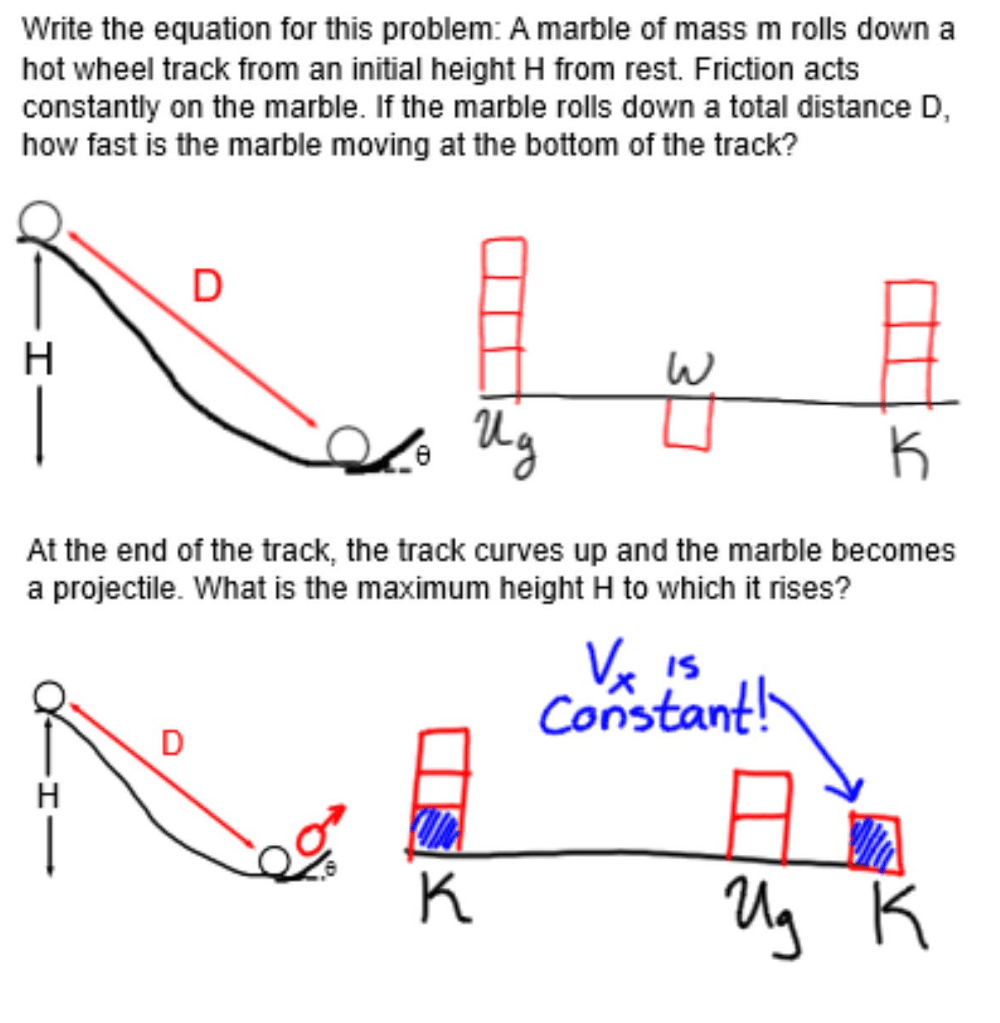

I want to press on the students that there isn’t an “equation” for energy problems that they are looking for. They need to determine thee equation from their bar chart and physics they already know.

We will start with another example problem and generate the equation through the bar chart. Students then have the opportunity to try a bunch more iterations on their own. This is about the time I will do the hopper popper lab energy style.

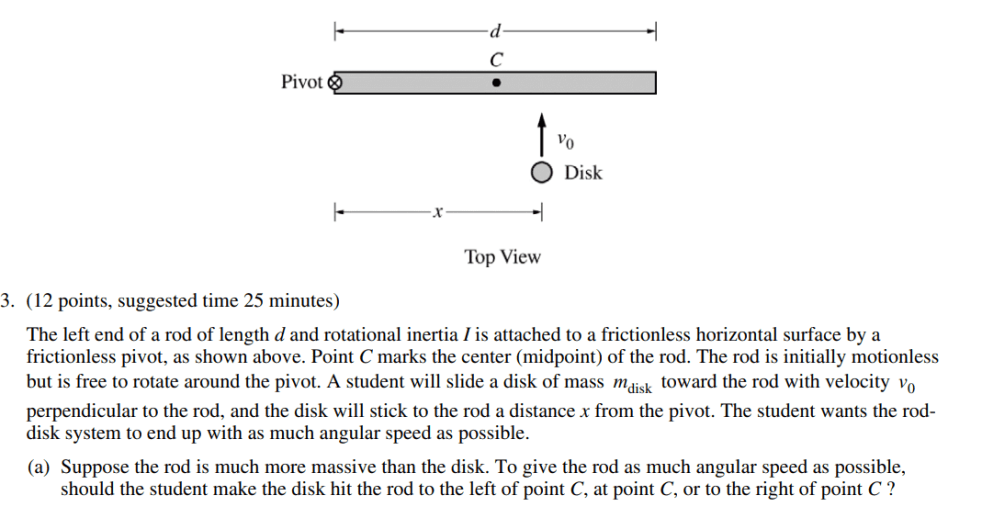

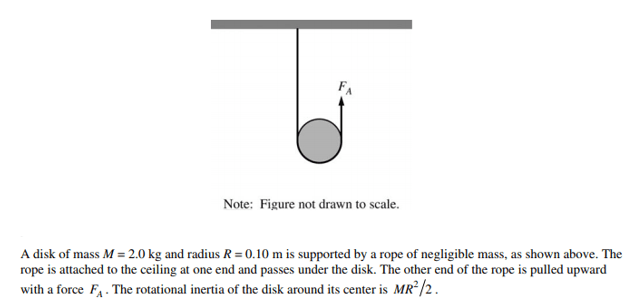

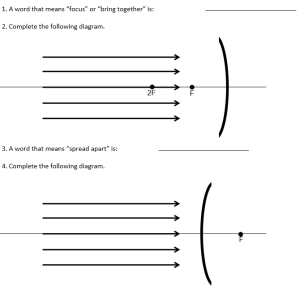

In AP I will open the following day a step further by giving them the problem below as a warm up (students do NOT have the bar charts provided!)

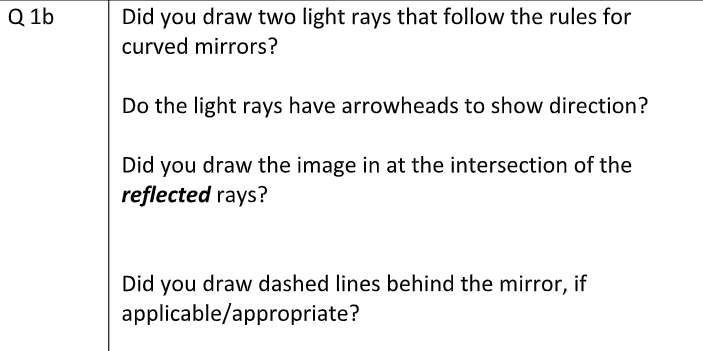

Students are first asked to create the bar charts because there’s no point in trying to write equations and solve for anything until the bar chart is correct. In the first part most students will neglect to include friction. In the second, students will say the ball only has potential energy at the peak, forgetting that the horizontal component stays constant!

The purpose of this exercise is twofold: first, it’s a great opportunity for interleaving. Second, it demonstrates to students they need to be ready for anything!

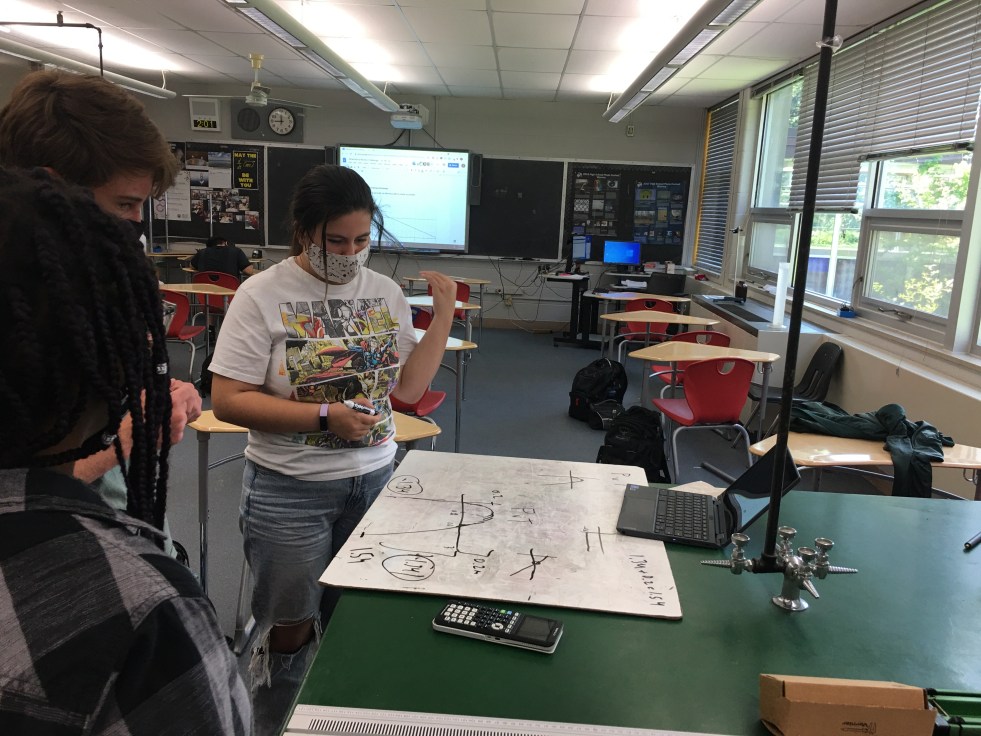

This year I’ve been incorporating vertical white boarding from Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics and it’s been truly amazing. After this exercise we went to vertical boards where students had two more problems, one was straightforward with friction while the other was solving for the height of a ramp needed so a ball can just make it around the loop.

The following day students engage in my conceptual whiteboard challenge where I help scaffold an expert approach to problem solving.

Next up, what my mathematical lab looks like for energy. Time to bring out the toys!

Turns out I also have a lecture video for this one (thanks COVID!)