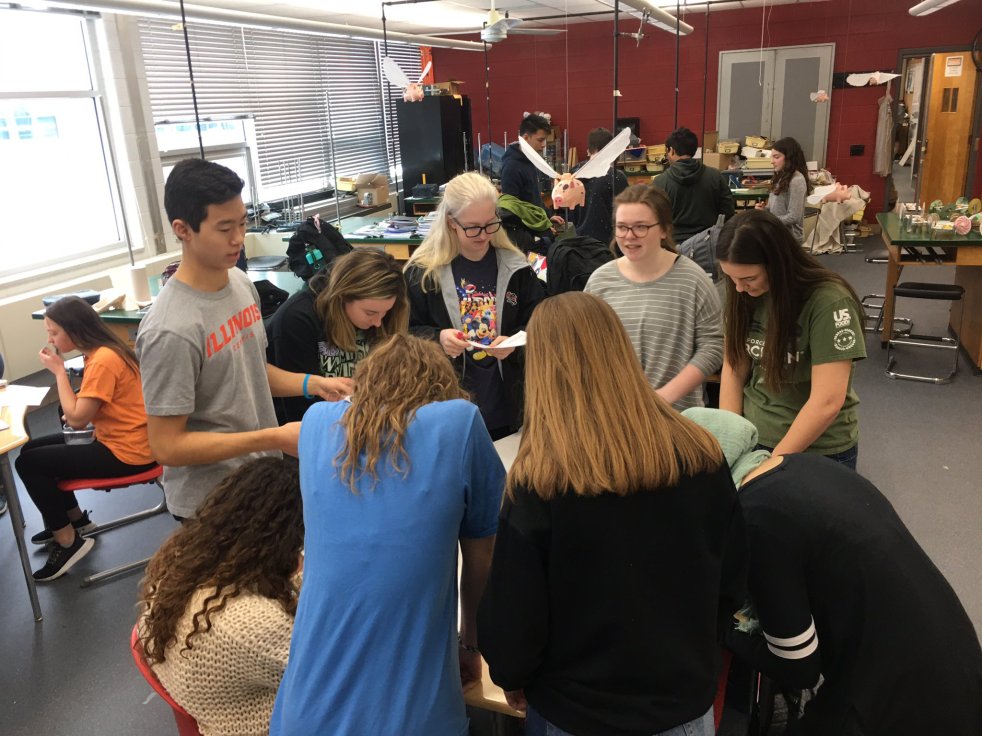

Physics Education Researchers know that active learning is better for students than lectures. At the same time, anyone who has attempted active learning environment knows that students do not always believe this to be true. The same holds true for study methods and habits. Instead students will balk and complain that “my teacher doesn’t teach”. Most recently a student told me they believed that by asking them to actively learn and collaborate, “the burden of the teacher has been placed on me”. I believe it was at this point I was ready to post Rhett Allain’s Telling you the Answer isn’t the Answer on every tangible and virtual learning environment I occupy. I didn’t do that.

At the end of Chapter 6 of The Science of Learning Physics, Mestre and Docktor share that students should learn about the research surrounding effective studying. I would argue that the same should be true about the active learning environment. In the past I have mentioned this casually to students, however the challenges of COVID required me to shift casual mentions to intentional direction.

Brian Frank shared that Jennifer Docktor had a webinar on the book. Excited and curious I watched the video. I was most excited that it was only 30 minutes, meaning it would be digestible for my students. The talk is an overview of the highlights of each chapter of the book. If you haven’t already ordered it and are interested, this is a great entry point!

Shortly thereafter I assigned the video in google classroom and provided the following:

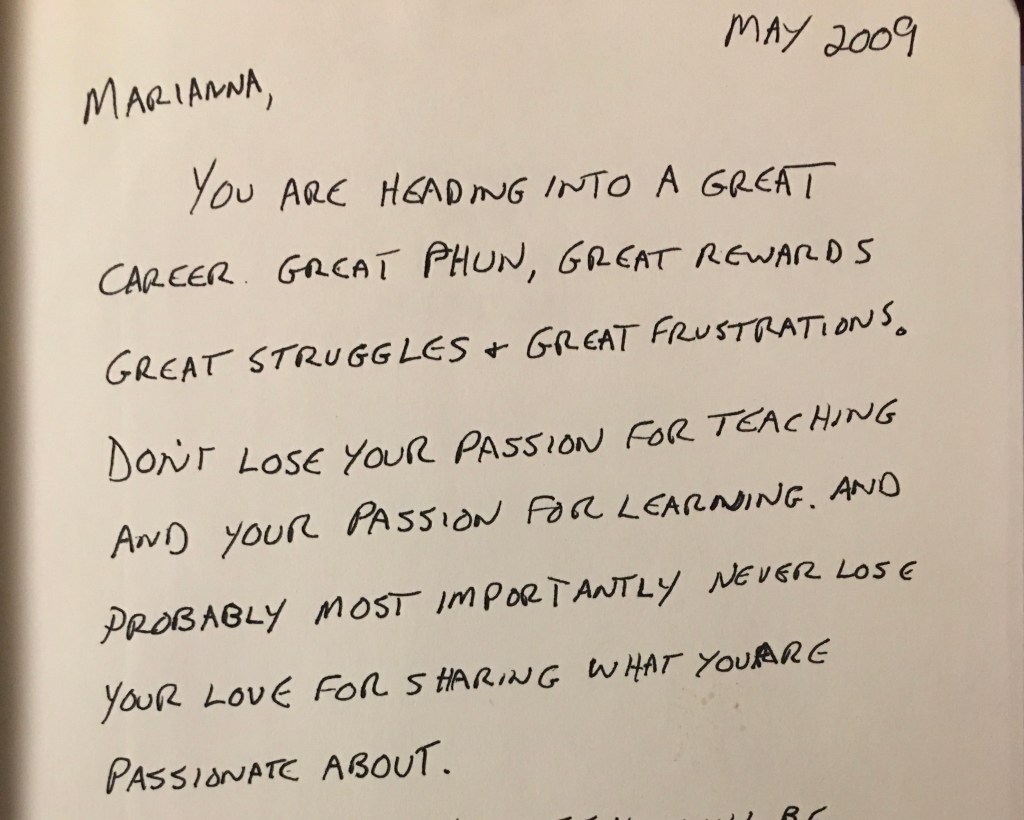

- As you prepare for finals and reset for semester two, I’d like you to listen to this talk by Dr. Jennifer Docktor.

She is a professor of physics at UW Lacrosse and recently co-authored a book about how students learn physics.

Watch the talk and write a short reflection. Include the following. Remember, you should be digging deep and synthesizing, rather than simply agreeing or disagreeing.- What resonated with you?

- What ideas challenged your current thinking about how we learn and learn best?

- What do you now wonder after listening to this talk?

- What resulted in an “aha” moment for you.

- Lastly, as a student, what can YOU take away that you’ve learned in order to improve your learning next semester?

I will be completely honest. I have a few students who have been extremely verbal about their hatred for active learning. I read their reflections last. I was also nervous because as a teacher, I’m a life-long learner. There are components that Docktor discusses and shares that I haven’t yet implemented or perfected, especially thanks to the COVID monkey wrench. Would students call me out? However, I was really impressed by what the students had to say.

Some students reflected on recognizing the intentionality put into our classes:

“I like our weekly practice tests, but I didn’t know they had an educational backing. When she started talking about interleaved practice, I thought about the momentum problems with a twist and some other homework problems that we’ve had.”

I had several students comment about applicability and connections to education outside of physics

“I now wonder, after listening to this talk, if other fields of science education, and other education in general, put this much effort into how material is taught to students, or if I have just never been aware of how I am being taught in the past.”

Another student actually posed that physics exposure happen at the elementary level so that kids have a better scaffold of experiences, rather than needing to uproot firmly held misconceptions in high school. (Big YES to that!)

What I really enjoyed, however, was students seeing themselves in the studies. Many students admitted to equation-hunting rather than starting with the big picture. I found this particular statement to be really fascinating about why they default to equation-hunting,

“I do this myself sometimes the reason why I do this is when I don’t feel confident in the work or I don’t know what I’m doing.”

Students overwhelmingly reported that an idea that resonated with them was how they are not blank slates, and experiences shape misconceptions. They saw themselves in the research and were shocked (and in some cases bothered) to hear that lecture and note-taking are ineffective, along with many of their tried and true, but passive study habits. One student who has been particularly insistent shared “the studies she talks about seem to prove me wrong about the lecturing method being more effective”

After completing this excersise here are my lingering questions:

- Given the demands of AP 1, how can we encourage students that they are growing and learning by leaps and bounds, even if they aren’t at a 4 or 5-level for AP yet? I feel this is easy for me in my non-AP courses because I set the bar, and so I can raise the bar as the year progresses, without students realizing this has occurred.

- Many students shared the sentiment of “well everyone is different, and this doesn’t apply to me” neglecting that this is a large body of work and research spanning decades and involving thousands of students. I’m wondering if more work in the realm of cognitive science and how we learn would be beneficial. But how to weave this into the structure of my courses?

I’d love to hear your insights!