I returned from doing work at the district office to a disaster.

My students were supposed to take their “check-in” (that’s what I call quizzes because their function is to literally check in on student learning) and at first glance I was walking into a mess.

Students should of had enough time to finish the two problems, however the vast majority of my class had half of the assessment blank.

I started looking at the students who finished.

Only three.

All three had done great!

But I have 30 students in this class. Not good.

At first, I will admit I was really upset for a number of reasons.

So I started planning what we were going to do. When I looked more closely at the assessment I noticed that about two thirds of the class was actually doing pretty ok, they just needed more time. Regardless of the fact that I felt strongly that they had enough time, I couldn’t argue the evidence that what was complete was good.

The students who had not done anything beyond opening the assessment were the same ones who have been disengaging with the material and straight up refusing to attempt. As much as I was frustrated that this was on the student (because, after all, my other class is flying and the students who are doing things every day are succeeding). I took a deep breath and regrouped.

What if I made it tactile?

We’ve been working on multiple representations for momentum. So I made up little squares to represent units of momentum. I made a set of red and blue (for each car) and added labels for 1 kg across the bottom and 1 m/s upward.

Within table groups I assigned group roles that I borrowed from Marta Stoeckel (check out her article with Kelly OShea!) and then also added a task, one representation needed to be done by each student in the group on the large white board and then they were all responsible for doing it on their own paper.

Step by step we worked through the original problem in small groups. Since I had reduced my “class size” to eight, I was able to give the students with the most need all the attention they needed while the rest of my class completed their assigned tasks.

One of the cool features, aside from students commenting that they liked placing the blocks, was that it allowed us to discuss the limitations of using discrete blocks. In the assessment problem the final velocity was 3.6 m/s, so while I had some students show 22 blocks, demonstrating they understood that the total momentum was constant, they had uneven heights for an inelastic collision. It’s better, then, to just label height and width and go from there.

By the end of the hour everyone was happy.

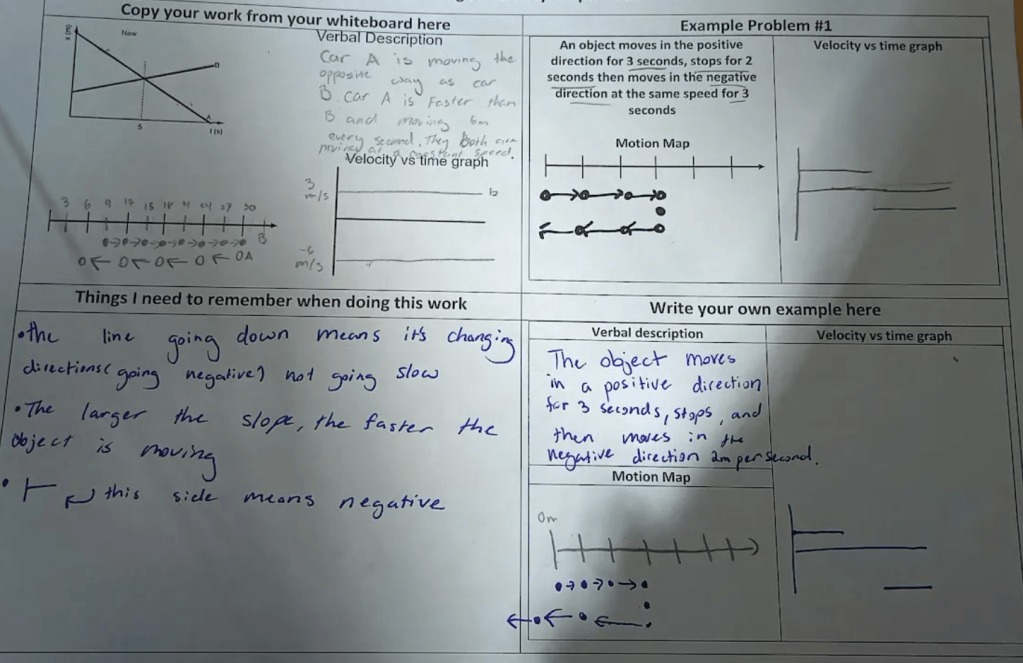

My three students who did great were given this handout. They were asked to come to consensus and then reflect on their gaps/needs. I checked in with them at the end and they were able to communicate confidence and what they needed.

The large group felt satisfied that they had the chance to go back into their assessment. When I went back in to review the work I found that their performance matched my previous hour, even though they take more time.

The small groups were kind of amazing. Most of these students had been really checked out, but this small shift got pretty much everyone fully on board and verbalizing that they understood what was happening. In order to make up for the assessment, a second problem was on the backside of the worksheet for them to do independent of my help.

At the end of the day I reflected on how the only reason I was able to do this on the fly is due to the fact that I’ve been teaching for a long time. This was a new-to-me activity (although I’ve set up differentiated groups like this before) but at the same time this was effectly three different lesson plans in the same space. Elementary teachers might laugh at my overwhelm, but the reality is that teachers (all of us) are simply not given the kind of time required to plan high quality experiences for our students. This also shows how important data is in our work. Data can allow us to be a bit more objective in our judgements, moving from “they didn’t do anything” to “what else could I try to fill their needs?”

This job is challenging, but it wouldn’t be fun if it wasn’t!