I did it. I finally revised how I teach momentum conservation to my on-track physics students and I’m never looking back!

It can be really hard to shift something that “works” especially if you don’t have a team. For my on-track physics students collision/explosion problems were always an “easy win” for students. We would define that “momentum is conserved” and then talk about how to solve the problems. I would lecture and show them the “table method” and then the “brute force method” and allow them to choose how they wanted to solve.

This was satisfying for students. It felt easy and students gained confidence in physics. However I was always irritated by this. They were performing a series of algorithms to get to an answer with no real understanding of the underlying ideas.

Sometimes we don’t make changes until we are forced to. I had yet to see this part of momentum done in a way that was in alignment with my overall pedagogy and it “worked” …enough. However this year during this particular set of lessons I was to be observed in my classroom. I wanted to ensure that the observation showed who I really am as a teacher, rather than a snapshot of something I had yet to address. So I started digging.

I had seen some work with momentum bar charts around the twitterverse and in Pivot Interactives and in the modeling community, but I wasn’t entirely sold on it. It felt like taking a good idea from energy and forcing it into a place it didn’t need to exist.

I looked to see what Kelly Oshea had done and found her momentum card sort, but I knew that would be too much for an introduction to the content, but it got me thinking.

The following set of four representations is what I settled upon, and here’s how it went:

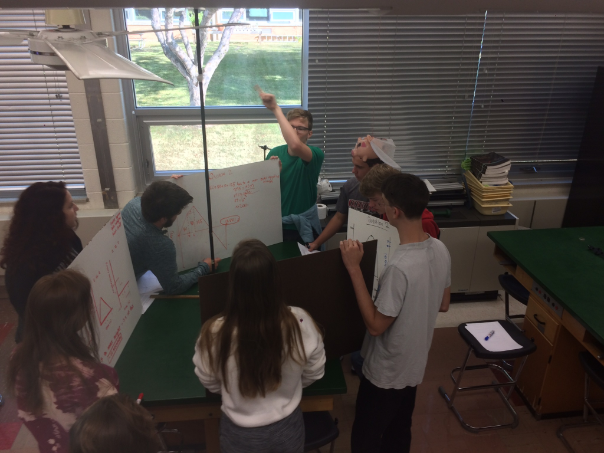

First, for each of these I would demo the collision first so students had an idea of what was happening before and after the collision. We spend one day on elastic, one on inelastic and one on explosions and for each day we went through several different examples. I’m going to use our final inelastic case for this post.

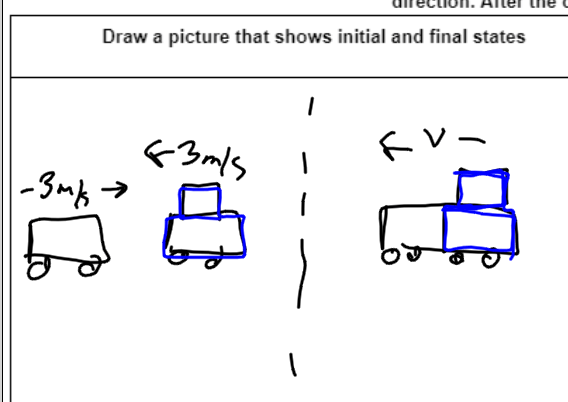

1 – Draw a picture

There is a reason why “a picture is worth a thousand words”. A picture allows us to easily see and locate information that we might miss in text. For example, in this problem it becomes clear that we have some direction issues, so we know that negatives are going to come into play. For the purposes of my pictures I draw my more massive cars with the added mass on top. You’ll notice I’ve also color coded the larger car as blue.

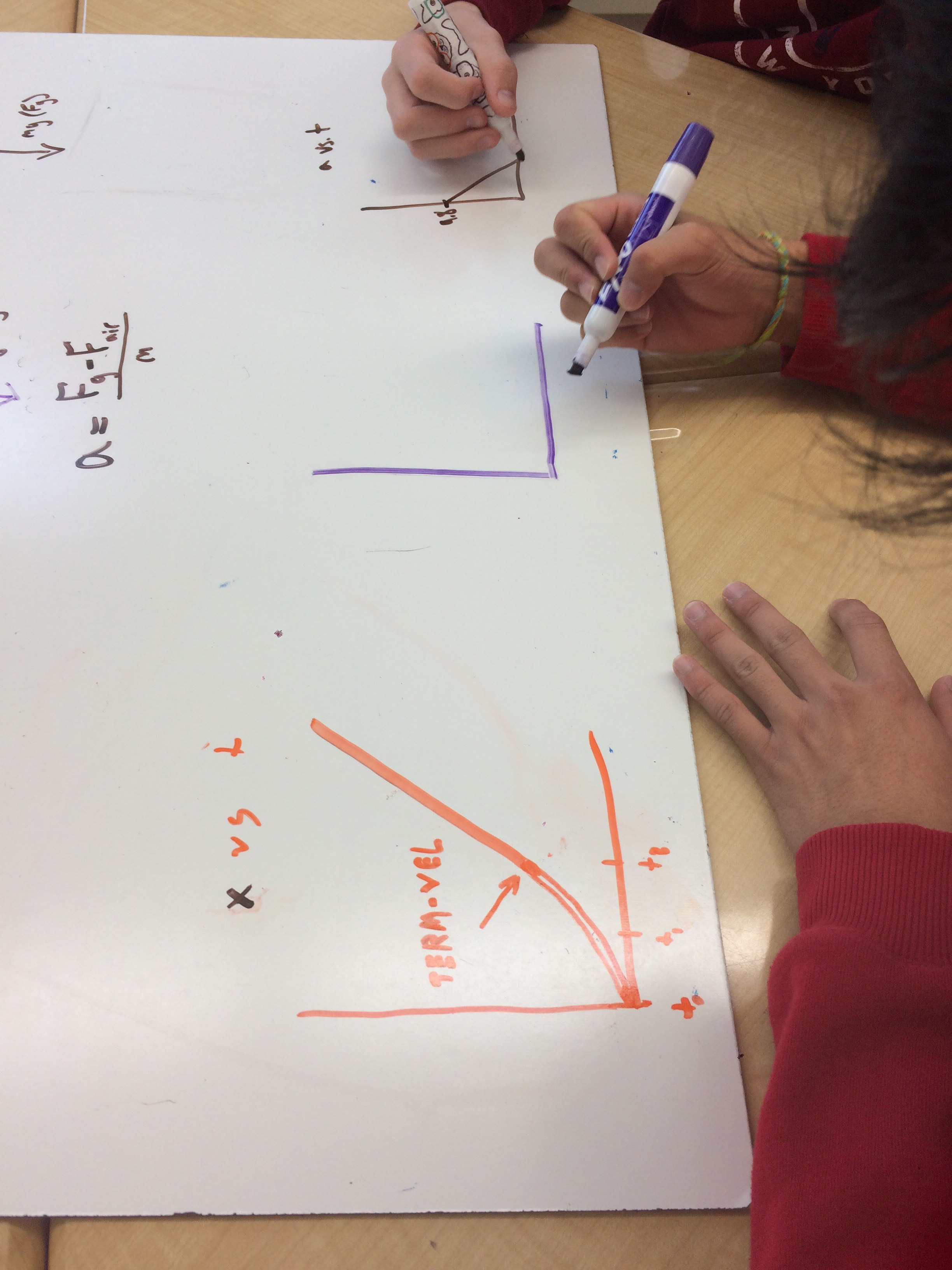

2 – Momentum Bar Charts

I finally decided to implement the bar charts. For my intro problems I used whole numbers so that we could represent them with tangible “blocks” of momentum. The block width is the mass and the height is the velocity, so in this particular case the total number of blocks is the momentum. I found my students had a hard time shifting this to a more abstract view where you could use area so this will be an emphasis next time.

You’ll notice I’ve brought the color scheme over for the blocks. In class we have already discussed that the total momentum is constant. So we draw the initial case and then we discuss what the final case is going to look like in order to keep momentum constant. Students are able to recognize that we have a total of -3 units of momentum on the initial side, so we need 3 in the final. Since this is an inelastic collision the width has to be three which means the height can only be -1. Students are already solving collision problems without realizing they are doing math! This felt like a really cool win.

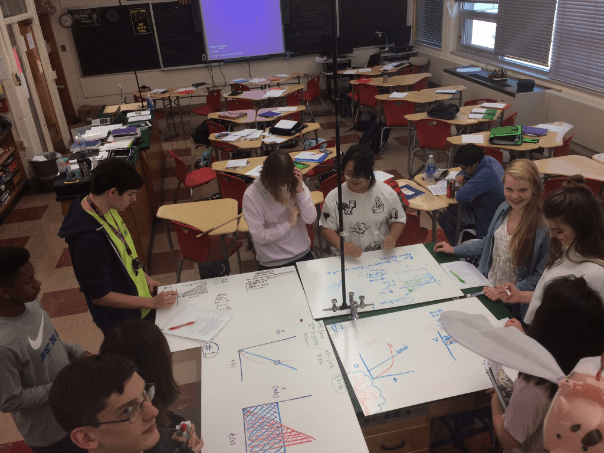

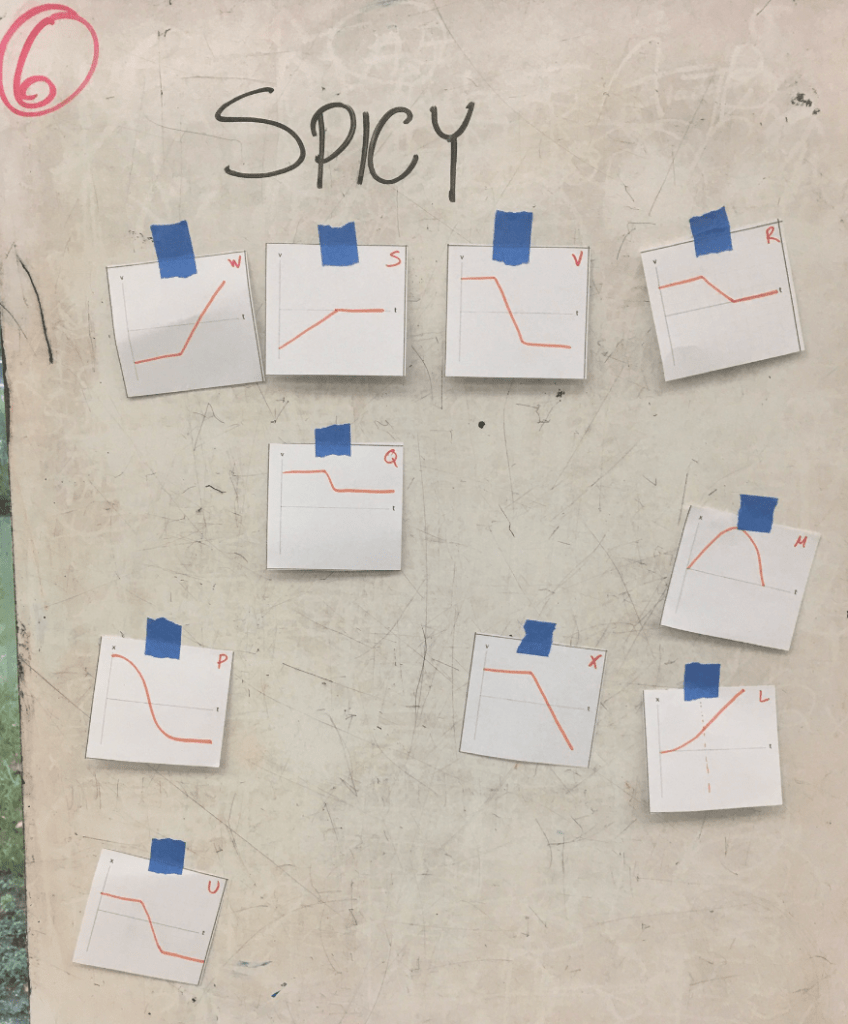

3 – Momentum vs time graphs

This part is something I need to think about a little more. It was something that was “obvious” to me, but was very much not obvious to students. To me, it was “obvious” because you just slap those initial and final values on the graph. The hard part, I thought, was ensuring that you are accounting for each car in the inelastic case.

I absolutely LOVE this representation because this is where students can SEE WHY momentum is constant. The CHANGE of each object is the same size, but different in direction! It’s super satisfying!

The challenges my students had came from notions about what it “should” do. Because the cars are moving together, they want the lines to go together at the end. When I recognized this, we spent a day looking at the representations as a whole and locating where momentum is represented in each in order to construct this graph of momentum. There were a lot of “ah ha” moments when we did this. I think next time I will save this graph for last.

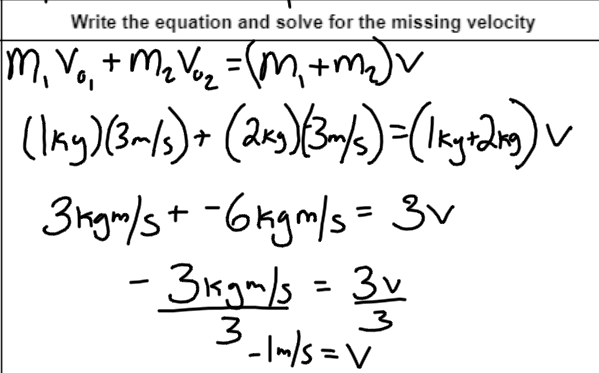

4 – Mathematical Model

The tables are no more! With this mathematical model right next to the other representations, student can see where everything is coming from. The momentum terms, the momentum values, and the final velocity value at the end.

While this was definitely a harder task for students to complete, I feel a lot better about their conceptual understanding of what is happening in a collision. The multiple representations also mean that students have multiple ways of showing me that they understand what is happening.

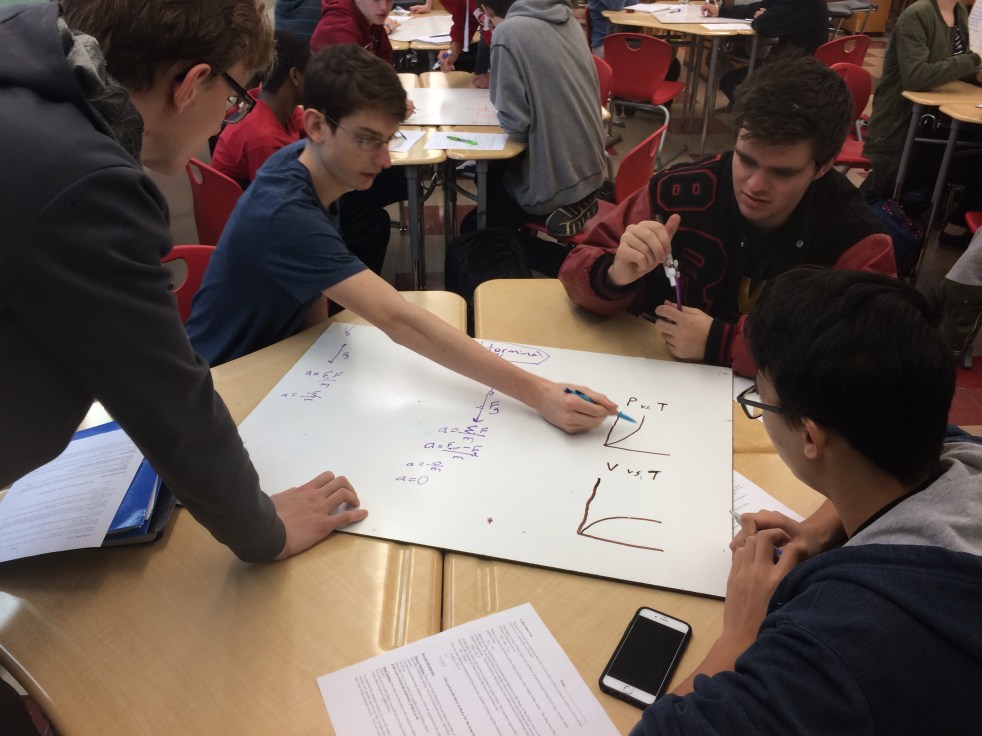

It was so cool to watch them work, discuss and argue. The FBD’s were relatively easy, the discussions mostly about whether or not to put air resistance on the t=0 diagram.

It was so cool to watch them work, discuss and argue. The FBD’s were relatively easy, the discussions mostly about whether or not to put air resistance on the t=0 diagram.