I like to be challenged. In the last year as the Science of Reading has surged in use/popularity so too have the direct instruction advocates. Specifically in my space I’ve seen a lot of attacks on student-centered instruction (the type of instruction that is promoted by the National Council of Teachers in Mathematics and the NSTA) which argue that an emphasis on student thinking and problem-solving is harmful to all but the top tier students.

None of us educators who truly care about the craft are blindly and deliberately acting every day in ways to exclude students. Most of us are intentionally considering what is presented to us and how it impacts our students in the classroom. I graduated college fresh on the latest expression of inquiry-based learning making its rounds as all the rage. At that time the idea was to let students explore and then let them go where they wished. This concept drove my first day activities where my students play with various demos and lab set-ups, but it was very clear that the kinds of questions and ideas students would come up with on that first day were predictable and lacked meat. True to the advocates of direct instruction (DI) and grounded in cognitive science, the more you know the better questions you can ask.

My first year teaching was also a shift from my previous experiences in affluent schools to one where the majority of my students were highly dependent learners, for various reasons. I quickly realized that I needed to scaffold most of the resources I had from student teaching in order to support students reaching the intended goal.

In the years that followed I had a wealth of opportunities with student groups. I ended up teaching everything from co-taught freshman physics to honor’s physics at that first school and then everything from kindergarten astronomy to middle school integrated math at Northwestern’s gifted enrichment programming. Then I was back at my old high school where I tutored over 2,000 different students in science and math. That experience was eye opening in terms of how instruction impacted students, and yes, some students need more direct support.

I attended my first Investigative Science Learning Environment (ISLE) in the summer of 2018 and it was earth-shattering. Roughly a decade into teaching and the method from Rutgers University gave language and research to many of the things I had figured out along the way.

In 2022 I discovered Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics and in 2023 I attended a workshop with the author, Peter Liljidahl. At that workshop we focused on the later-half of the book which is arguably the most difficult to understand how to execute from the text alone. Peter explained to us that in their research what they noted was that consolidation and note-making were the critical components that made the different in lasting learning. Let me reiterate that: Peter himself shared with us that random groups, vertical whiteboarding, thinking tasks are easy to implement and certainly promote engagement but in order to get the learning to stick, the consolidation was key.

I started thinking about this in the context of any kind of active learning environment. In ISLE students go through the process of observational experiments and testing experiments and are also “representing and reasoning” along the way. After each round students are supposed to be “interrogating the text” and then practicing with problems. This works great for my gifted AP level students, but as many of us have found other student groups need more scaffolding and support. During the workshop Peter shared his latest idea for note-making.

Some context from the book. Everything is about considering the psychological messages we send to students about our expectations and their roles, and how we can make moves to flip that to re-center the student and their thinking. As renowned cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham points out, thinking is hard and our brains do everything possible to avoid it. At the same time we also enjoy puzzles and figuring things out (did you do wordle or connections today?). In the book the idea is that notes are something that happens after engaging with thinking and in a way that you continue to think while making (not taking) the notes.

Think about that for a second. When you take notes in lecture how does that go? Are you furiously copying everything and then find yourself not remembering the actual lecture? Are you trying to furiously copy and then falling behind, leaving you frustrated? Or do your prior experiences prohibit you from taking any notes at all so you give up. We know that the act of note taking is helpful for remembering, but there are also a lot of barriers and challenges when trying to get a group of 30+ individuals to all obtain the information pertinent to their learning.

The book discusses having students “go make notes” and to write things down for “their future forgetful selves” which is a good framing, but I noticed in class that many of my students were still unsure about what that would mean.

What it Looks Like

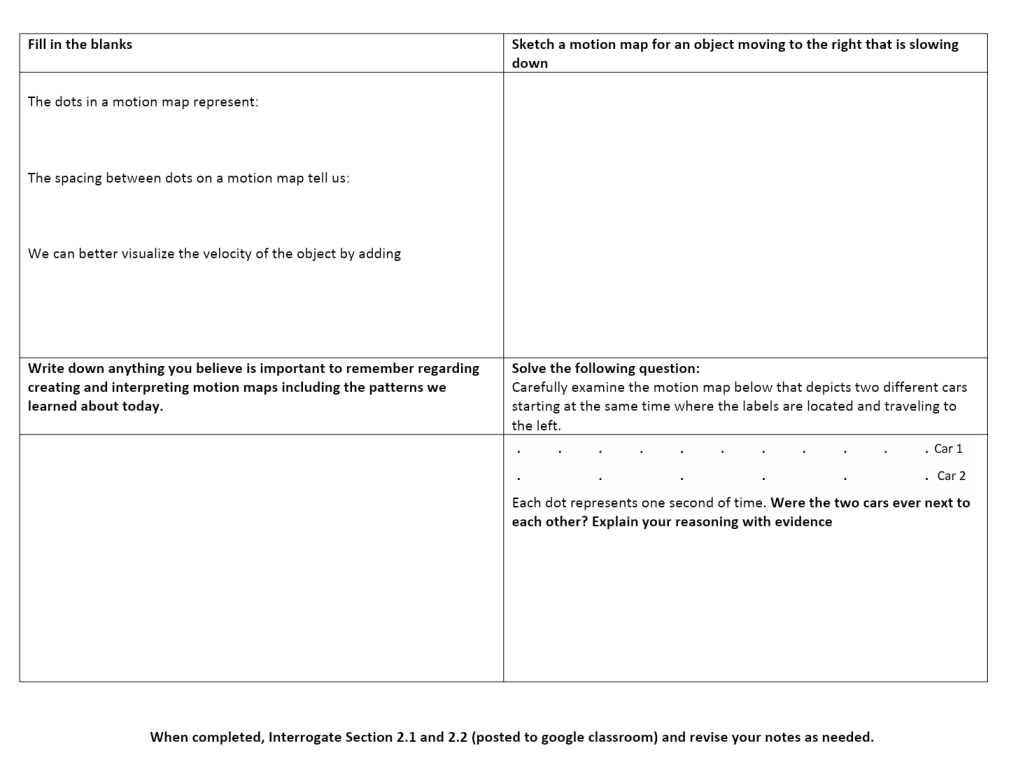

At the workshop Peter shared this really cool template (these are my notes from the workshop):

Check it out! It’s all the things the DI folks love to share are necessary and supposedly non-existent in a thinking classroom. The top is structured by the teacher. In fact, it’s two worked examples. The first is for students to fill in the blanks while the second is a similar, but different example. The bottom half is for student autonomy, though it should be noted that the “create your own example” can come from homework, the textbook etc.

The way this was presented was that students would create these notes on the whiteboards and then transfer them to their own notebooks. I cannot fathom running a lesson, and then doing the notes on boards and then having the transfer happen, so I needed something different.

Meaningful Notes in My Classroom

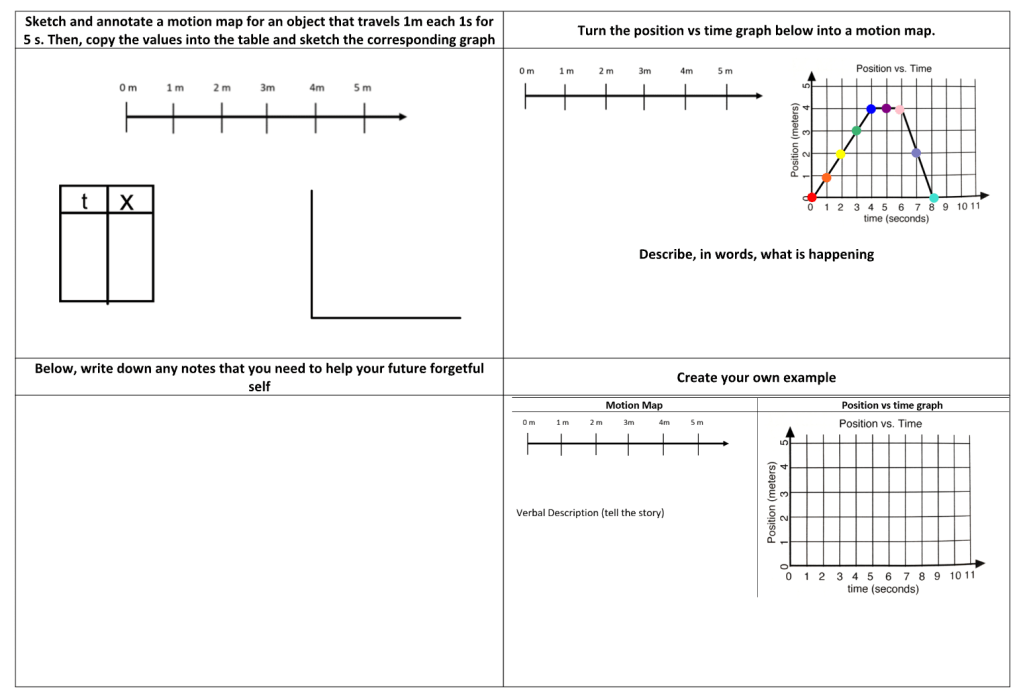

What I chose to do was to create the template and provide it to students with that teacher part already prepared. Here are a few samples:

This first set is what students completed after doing the observational experiements dropping bean bags behind a bowling ball and creating their first motion maps:

The following day I have students engage in a desmos sorting activity to continue working with motion maps as we continue the reasoning process. ISLE folks will recognize the content that is directly from the Active Learning Guides:

Next I borrow from the AMTA curriculum to start translating representations. The top half of this page was all work we do together on whiteboards.

Here’s what’s been really cool about using this style for notes:

- Students (and I!) are able to recognize what actually translated/processed during the class discussion. Since the first box is often work that was exactly from the discussion and whiteboarding we can hit those problem areas right away using the discussion we just had.

- The example is manageable. Instead of giving students 5-10 practice problems, they have just one they are required to complete. This example is either very similar to an example that was done in class or identical to the example done in class, but the example is no longer available to copy (yeah, I’m sneaking some retrieval practice in!)

- As students work on the top half and we have those conversations about what they are stuck on or missed I’m able to say “ok, that’s something you should probably put in the things I need to remember box!” This is also true any time I hear a student go “oooooooh!” when the lightbulb turns on.

- Create your own examples are actually pretty decent! Sometimes they are pretty similar to the first example, other times I see students stretching themselves.

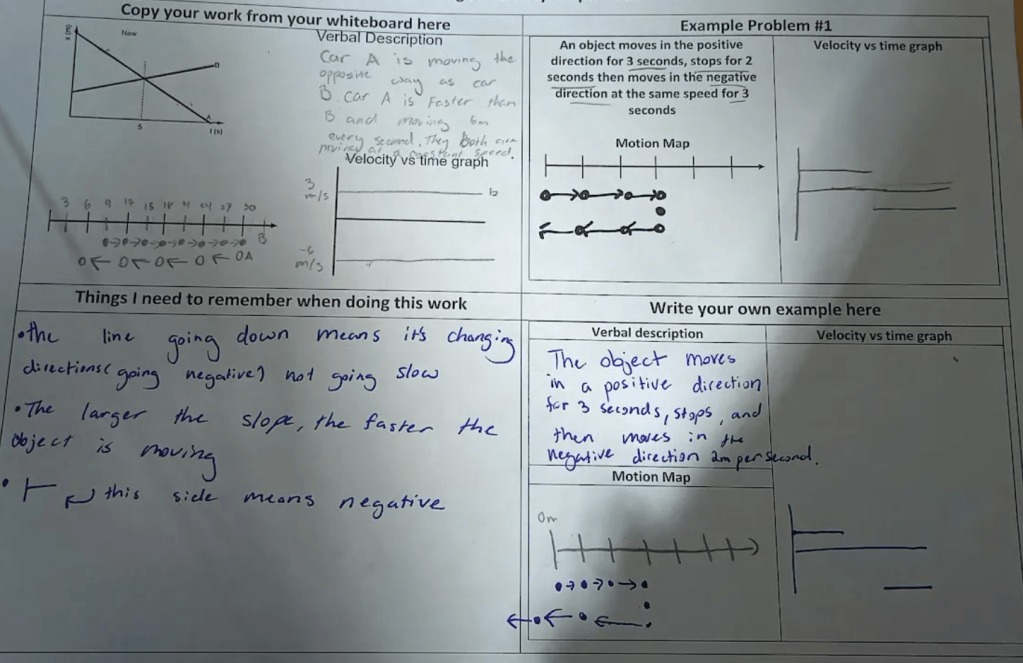

The notes that get submitted also paint a great picture of where my students are at. Check this one out. This student is pretty quiet in a class of students who are generally super vocal and asking for my help frequently.

I’m able to make a few judgements here from the work. First, this student doesn’t yet understand how to represent stop on the velocity vs time graph. Second, even though that’s the case, she does have a pretty good handle on what they were supposed to learn in the lesson that day (see the “things I need to remember”)

I’m still experimenting with this and finding ways to adjust and ensure that students are ultimately getting what I want them to get from the notes. I do feel, however, that now the notes that are on the papers are resulting in more meaningful work than when I’m expecting them to copy as I work on the board. I can still craft these so students get what I want them to get on the paper, but also provide space for autonomy and small wins to build confidence.