You know how I feel about online work! (Looking for Physics Classroom Companion Worksheets? Find them Here!)

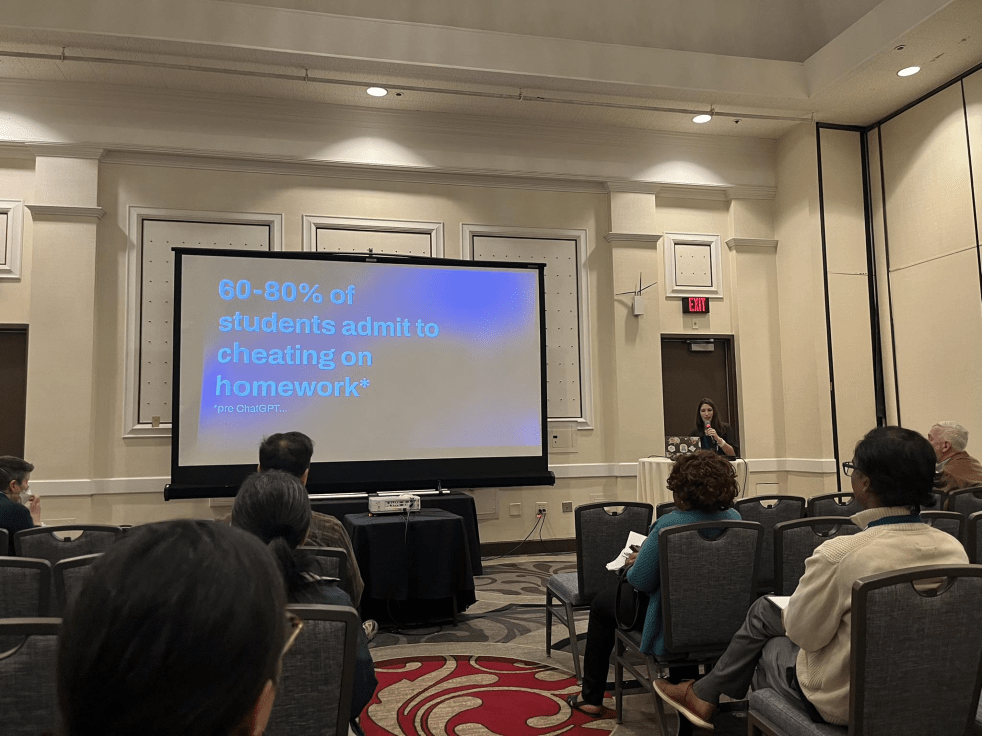

When I took high school physics almost everything was online. From physics classroom assignments, to the dreaded WebAssign, it was online. And because it was online, I like others, gamed the system (pre chat GPT). You know a certain number is going to show up somewhere in the answers? Enter it in all the blanks for the first submission so you can focus on the actual calculations. On the flip side was the part where you tried the problem so many times by the time you got it right you had no idea what actually worked. For the better part of my career I’ve been vehemently against all forms of online homework. There’s something about that screen that just puts a stop to the idea of using scratch paper for novice learners and we can’t have that!

(For what it’s worth, when AP went all digital I did NOT feel the urge to go digital in my classroom. I continued to do everything on paper. When APs came around I found my goal was acheived: I proctored the macro exam and did a count. 80% of physics students were using their scratch paper during the exam, while only 30% of non-physics students used their paper.)

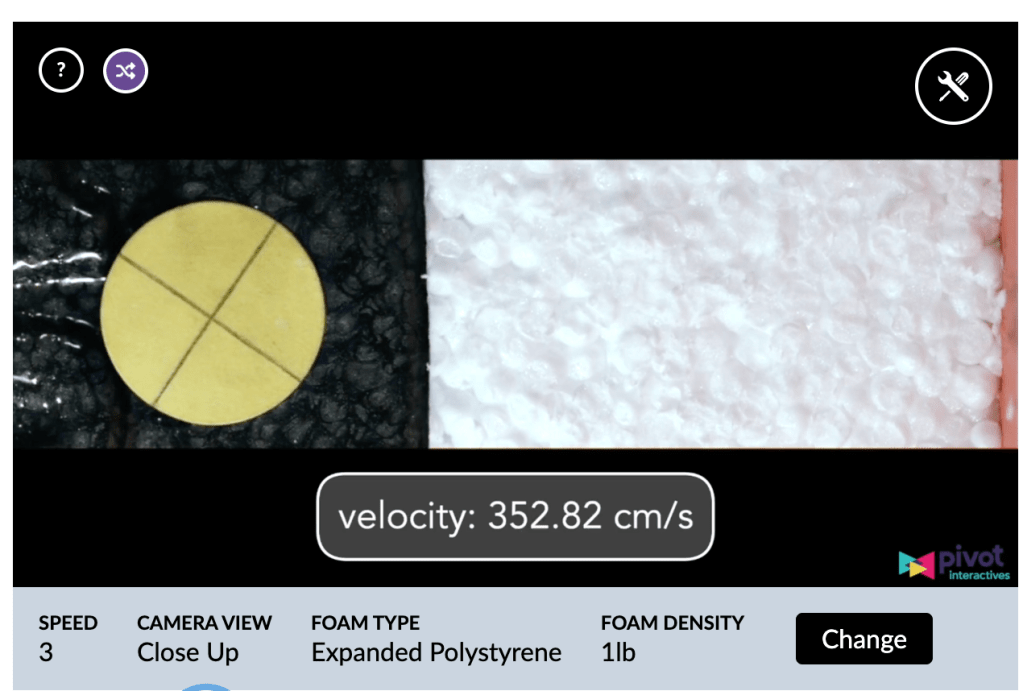

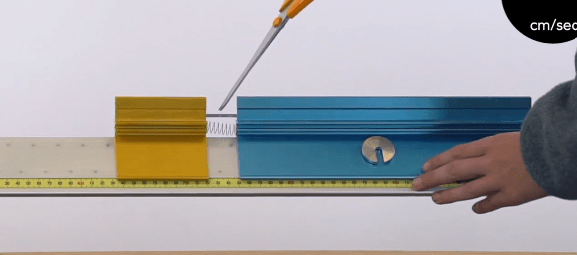

The first exception I made to online learning was Pivot Interactives. I was using Peter’s work back when they were “Direct Measurement Videos” which meant I had paper copies originally, anyway. As Pivot upped their game (including deep randomization and autograding) I started using some of these assignments since it sure made my life easier!

However, what I’m finding with my students this year is that like my Webassign days, students are doing the minimum to get all the green checks. This looks like not reading the prompts that explain what they’re about to do next and why, not actually collecting the data for the graph and totally missing the connections between the sample measurements and the data collection.

So, I’ve started to reimplement some paper versions.

The Activities: A Journey of Trial and Error

Earlier this year I assigned the helmet collisions activity. I added a prompt at the end that requested students to do the following:

- What was the purpose of the activity?

- Describe the procedure for conducting the investigation

- Describe the calculations you made and why we made each calculation. You should include details regarding your values!

- Describe what we learned from this activity about helmets as it relates to the impulse-change in momentum relationship.

This was ok, but I, arguably did this a bit hastily. I realized I wanted these documents handwritten and maybe a bit more depth/scaffholding.

A few weeks later I assigned the Explosions (Not Really) activity.

I knew that students would totally ditch all of the methods we had been using, so I decided to give them a paper to complete before the activity that related to the activity. This required them to complete the calculations with similar, but easy numbers and then have me check their work prior to the activity. This got a good chunk of kids on board, but some still struggled with the transference.

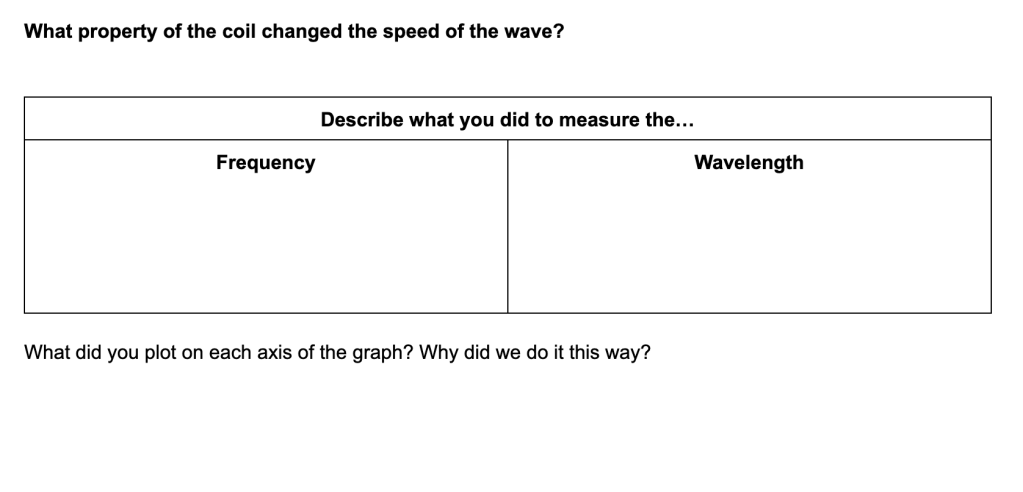

Still not completely satisfied, this past week I assigned the “Intro to Transverse Waves” activity. In this activity students are going to linearize a graph. This is a skill we don’t really cover in my regular level physics, but I like doing it at this point in the year because it’s such a powerful tool. As I anticipated, many students were ignoring the text about linearization completely. I chose a different approach to the paper copy.

I gave students this document which contains the following prompts:

First, I asked them to describe to me some of the new vocab as well as how we obtained our measurements

Next, I use a modified template from the Patterns Curriculum when students write conclusions in labs where we have graphs. It looks like this:

After investigating the behavior _______________, I conclude that there is a ______________________relationship between the [independent variable name] and the [dependent variable name] As the [independent variable] kept increasing, the [dependent variable]_____________________________. This system of a ___________________ can be mathematically modeled as:

[write the final equation]

where the constant [slope value] is the [description of slope for this experiment] .

I require students to write the ENTIRE paragraph from start to finish. This is not a fill in the blank activity.

This is currently my favorite interaction of the paper follow up and I’ll probably build more of these moving forward. I’m really in love with the patterns physics conclusions because it really requires students to put everything together.

Grading

I’ve noticed there’s a VERY strong correlation on these summaries between students who took the activity seriously and learned from it, vs students who did not. Because of this, the only thing I really need to grade with care is the conclusion paragraph itself. If students did the lab correctly, this paragraph looks great. If not, they usually don’t do well on this.

Do you do anything like this? What does it look like? How do you support genuine learning using online platforms?

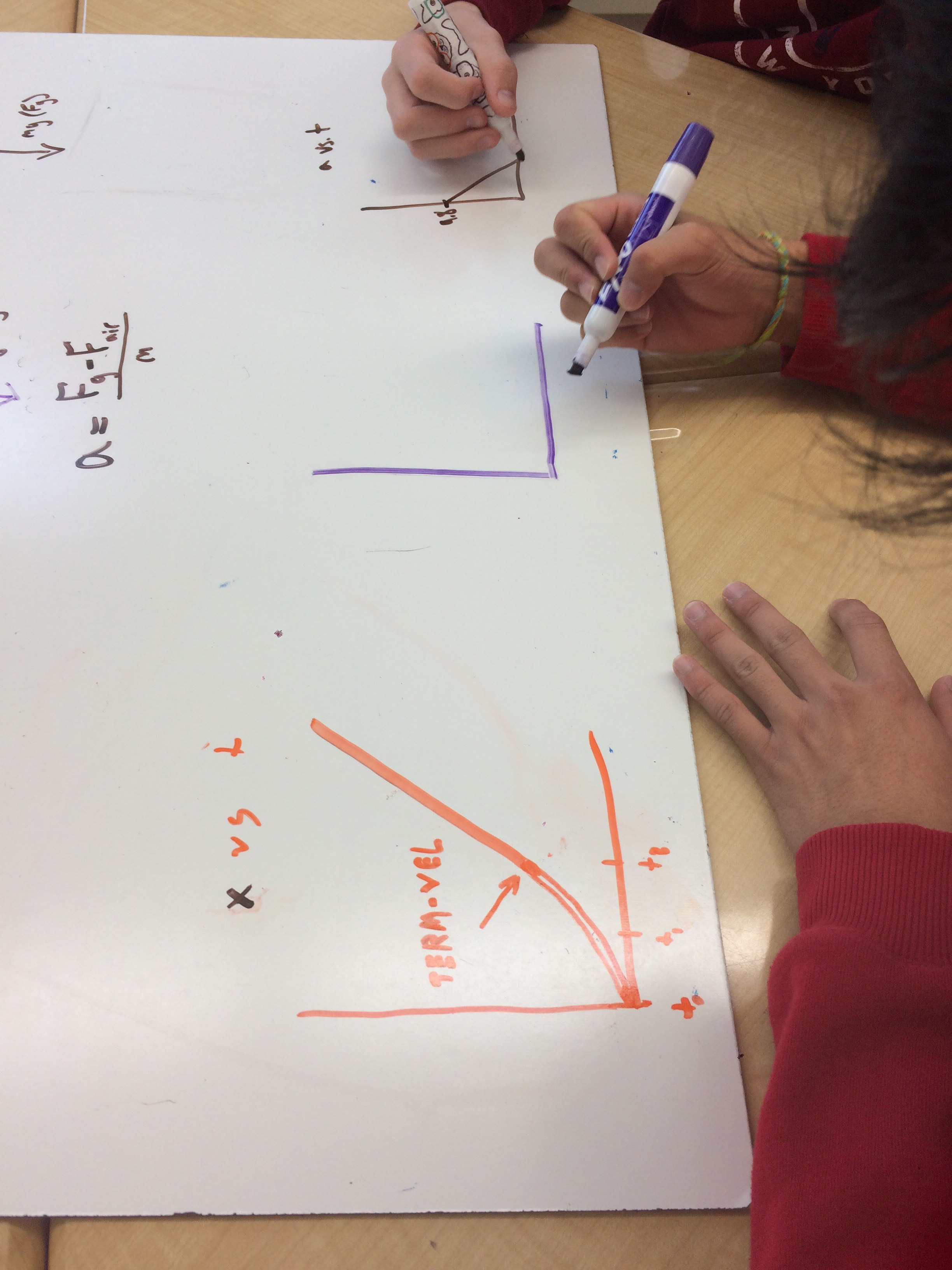

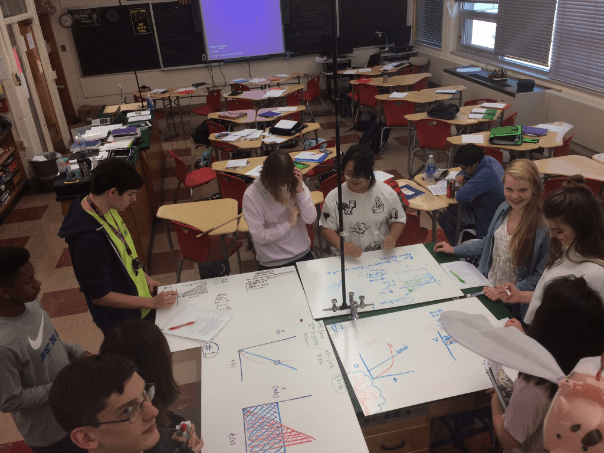

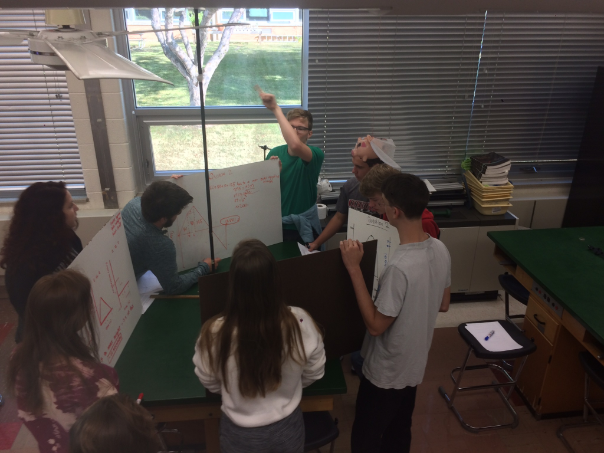

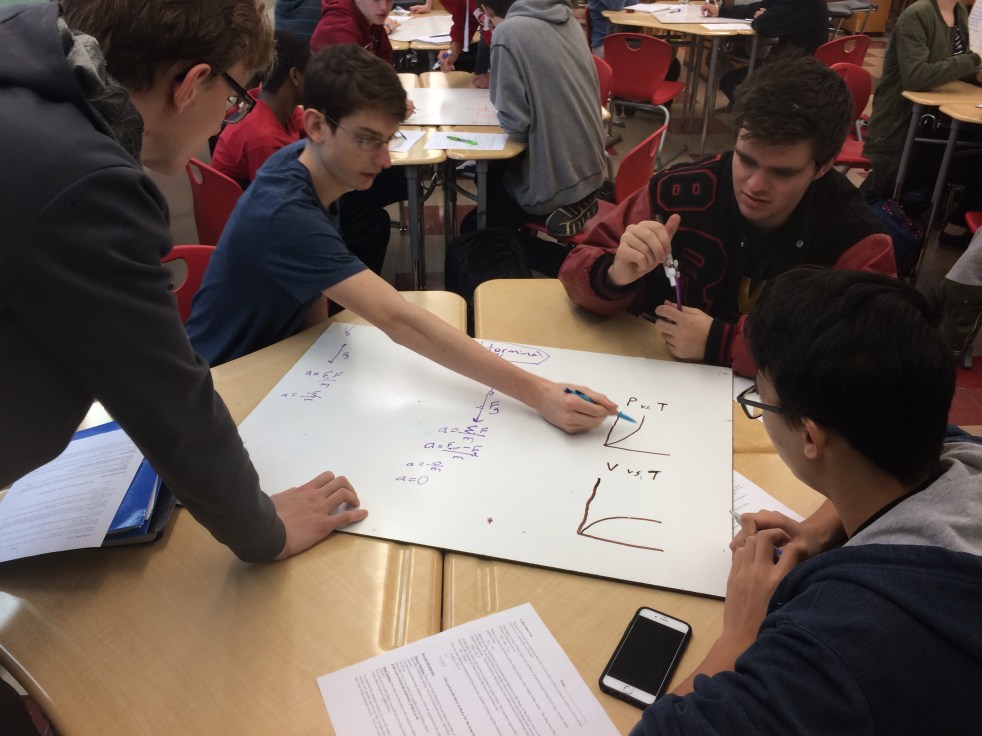

It was so cool to watch them work, discuss and argue. The FBD’s were relatively easy, the discussions mostly about whether or not to put air resistance on the t=0 diagram.

It was so cool to watch them work, discuss and argue. The FBD’s were relatively easy, the discussions mostly about whether or not to put air resistance on the t=0 diagram.