“You will be SO markatable”

“You will have NO problem finding a job”

“You’re certified in physics, chemistry AND math?! You can get a job anywhere!”

Those comments have all been said to me. Because, you know, I have a physics degree, I’m a woman, and I have a pretty cool set of experiences. And yet in 2011, when the recession hit the teacher landscape, I found myself sitting in over 20 interviews with no success. I spent the next two years working as a tutor after being rejected from the physics teaching job at that school and also teaching math at night school and chemistry at summer school. I was also teaching summers and Saturdays at Northwestern’s gifted program. All of these things together plus private tutoring scrapped together a decent salary. But after 20 interviews and no success getting a full-time teaching job…I won’t even get into what that did to my feeling of self-worth, especially when I caught a student from summer school telling her classmate about me, “she’s not even a REAL teacher”, a day after which her mom showed up “lost” so she could scope me out.

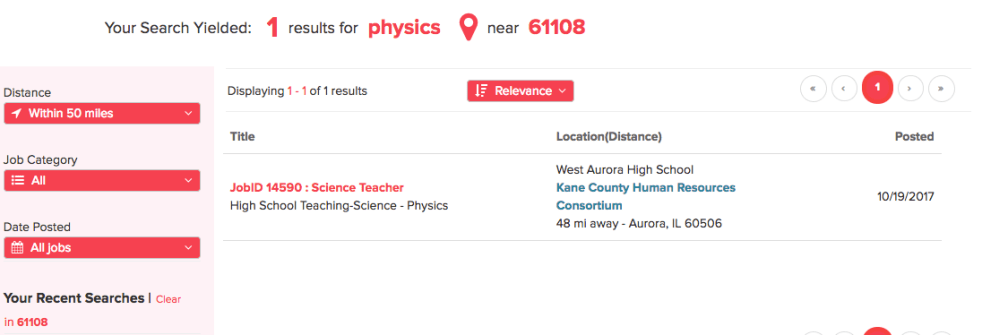

Here’s a snapshot as of right now within a 50-mile radius of where I live

That’s right! One job. And guess what is under the job description “chemistry endorsement desirable” Yep. This is not a 100% physics job. This is a physics job with a chemistry prep.

Mind you, there is no shortage of people here! My city is just under 150,000 people and our public school system consists of 5 high schools. There are numerous private schools in the area representing the Catholics, Lutherans and several other Christian denominations. There is one teacher in each building who teaches physics and I am the only teacher who gets to teach physics all day. I am also the only teacher with a degree in physics. (I am part of the 12% nationwide that’s a woman physics teacher with a degree in physics) The second sentence is the one that seems to get all of the attention by Universities and PER groups.

APS put out this report which doesn’t quite sit with me right. You see, they reported these findings, among others, regarding why individuals want to and don’t want to teach:

“by far” as the report mentions, the number one reason why individuals don’t want to teach is because they fear “uncontrollable or uninterested students”

The minute I saw this I questioned the results. WHO ON EARTH are they talking to? Well, APS, you got me to check out the whole report. Here’s who they surveyed:

Only 64 people who completed the survey are committed teachers of high school physics! Most everyone else involved was currently within the University setting (students).

Newsflash: You have NO idea what the classroom is like until you get there. Betsy Devos is a fantastic example of this.

Turns out, when you put a person who’s mildly competent at teaching and cares for the craft, the ‘disinterest’ and misbehavior are rather subdued. Make no mistake: it takes 3-5 years to get into a groove and to start to master the management aspect, but that can be said of most any job.

The report also discussed the various incentives people are given to go into teaching:

1. “Access to high-quality courses at my institution that prepared me to be a successful teacher.” 2. “All my student loans could be forgiven if I were to teach for 5 years.” 3. “Better teaching salary.” 4. “I would not have to spend extra time in school to obtain a teaching certificate.” 5. “I would be given free tuition for extra time spent obtaining my teaching certificate.” 6. “There are currently scholarships available for people in science and math teaching certification programs. Scholarships up to $20,000/year are awarded on the condition that, after earning a certificate, one teaches two years in high-needs areas for each year of financial support.”

No surprises here, but every single one of these is an extrinsic motivating factor. While usually somewhat effective in getting the ball rolling, it is hardly sustainable when the rubber meets the road and the nitty gritty nastiness of this job break forth. And let’s be real here, if it’s money that motivates you and you’re smart in the sciences, it doesn’t take too long before you realize an engineering job in the private sector is going to let you pursue your passion AND be up for raises AND get you 6 figures a lot faster. (and you get to pee whenever you want).

I would like to posit that there are three things that need to happen if we really care about highly qualified teachers in STEM

(1) We need to devote SERIOUS time, energy, effort and money into the teachers who care about their craft of teaching and get them the support to teach physics well. PhysTec is trying to do this and is providing amazing opportunities for teachers. We need more of this. New Jersey also implemented teacher training to boost physics in their schools. They actually see physics as the gateway to STEM careers. Turns out, the results were amazing. Not only has physics enrollment boomed, it has boomed amongst minority students, and their AP scores have boomed along with it.

(2) We need to advocate for physics and STEM education outside of our STEM bubbles. Too many of us are like our students, solving the problems we already know how to solve because it feels good. Telling each other about the importance of physics makes us feel good, but how much of that is getting out to the public? To parents? To students? To board members? To administrators? To politicians? Here’s an example of the difference in two districts:

District A has a strong STEM program, including an exclusive engineering academy. District A historically has offered Conceptual, Regular, Honors, Engineering and AP Physics C. There are 11 teachers who teach physics at some point in the day and although physics is not a graduation requirement, it is a norm that all students take physics before graduation. Since district A does not offer AP Physics 1, parents band together to ask the administration to run the course so that students who want to take an AP Physics can, even if they are not engineering bound.

District B has a weak physics program and would like to promote more students taking AP courses. However, district B refuses to run a course if less than 24 students enroll. None of the schools in the district are able to offer AP Physics. AP Biology runs sporadically. One year 20 kids signed up for AP biology but the district said this number was too small and canceled the course. Infrastructure is falling apart and although there is a 10-year facilities plan, staff have been told that they will only consider re-evaluating science rooms when they see if any money is left over.

These kinds of things go on all over the country. The simple matter of fact is this: unless a district is well-endowed with funds and/or parent advocacy, STEM is not supported on a very basal level. Because STEM requires space and equipment, which requires funds, and requires a continuous influx of funds in order to maintain the space and equipment and up to date texts.

Most of the folks way up high in school systems are pretty clueless when it comes to the needs of STEM classes. It’s not their fault, but if no one is truly advocating, they have no reason to funnel funds in that direction

(3) Our current physics teachers need to feel valued. They need great mentors. They need networks. I was really fortunate to have this “growing up” my AP Physics teacher was huge on intentional mentoring of rising teachers, he introduced me to Physics Northwest, which got me tapped into AAPT. From there I developed an amazing network of Chicago teachers. One of the teachers I met through this network, Shannon Hughs wrote an article in The Physics Teacher about the importance of this mentorship. Shannon probably doesn’t remember this, but at one of my first PNW meetings, she was sure to come up to me and tell me about an opening at her high school. The manner in which she approached me stood out and I regretted the fact I had accepted a job already. She was already putting to work what she had learned from her mentor. Then I moved an hour and a half away from Chicago and I lost this network. After 5 years of living out here I discovered the amazing community of #iteachphysics on twitter. It is these communities and mentorships that re-invigorate my passion for teaching.

Here’s the deal: no one goes into teaching for the money. We go into it for the passion. The passion of our subject, the passion to invigorate our students, the passion to see others learn and grow. The best teachers are these people. You can’t train that and you can’t crank that out of any big PER study or think-tank group. But there’s a catch…if I can’t do my passion every day, why would I stay in it? For me, it’s because my passion for teaching and students is greater than my passion for physics. If it were the other way around I probably would have finished the MS in electrical engineering I started in 2013 and I would be working in the industry now. Yea, that’s right, I was almost one of those numbers who left the field. Because the reality was that the field left me. I was moving to a place with no jobs and I had a department head who was almost begging me to join the department (this is a much longer story than is appropriate for this blog post). I am incredibly fortunate that I am in the position I serve now, it is literally everything I have dreamed of doing.

Pushing a bunch of physics undergrads into becoming high school teachers with extrinsic motivators is only going to create two things: teachers who lack the true empathy, patience and motivation to serve a student population and a bunch of graduates who think there’s a million jobs out there when actually there are just a handful. If they land one, chances are they won’t teach physics all day. In 2014 I taught 5 sections of Earth Science with the promise that if I took that job I would have physics the following year. I love teaching, but when I got those physics classes in 2015 after not being a physics teacher proper for 4 year, it was incredible how my motivation and job satisfaction sky-rocketed.

The very real fact is that physics is still undervalued. Everyone assumes it’s too hard and unnecessary. Much like the “Oh I never did well in math” statements that can cause math anxiety in children. Every kid who walks into my classroom walks in with fear and dread because they have heard horror stories. And yet, if they talk to any single student who made it past October, the critical 10-week learning curve, that student will tell you “it’s hard, but it’s fun” or “it’s hard, but you just have to think about it” I fight these preconceived notions tooth and nail every day, but when adults everywhere are telling them otherwise, they have no reason to believe the physics teacher that physics is a good place for them to be.

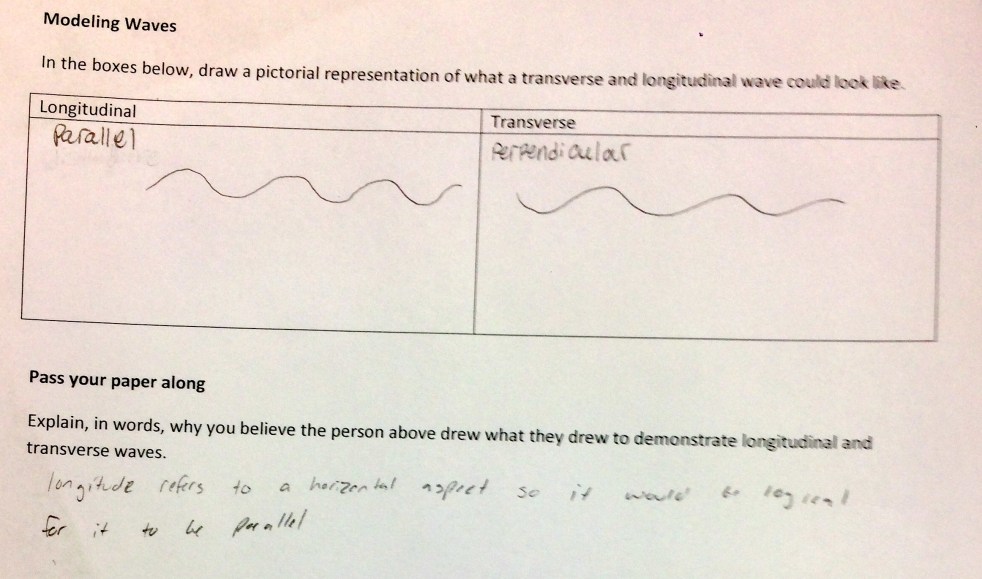

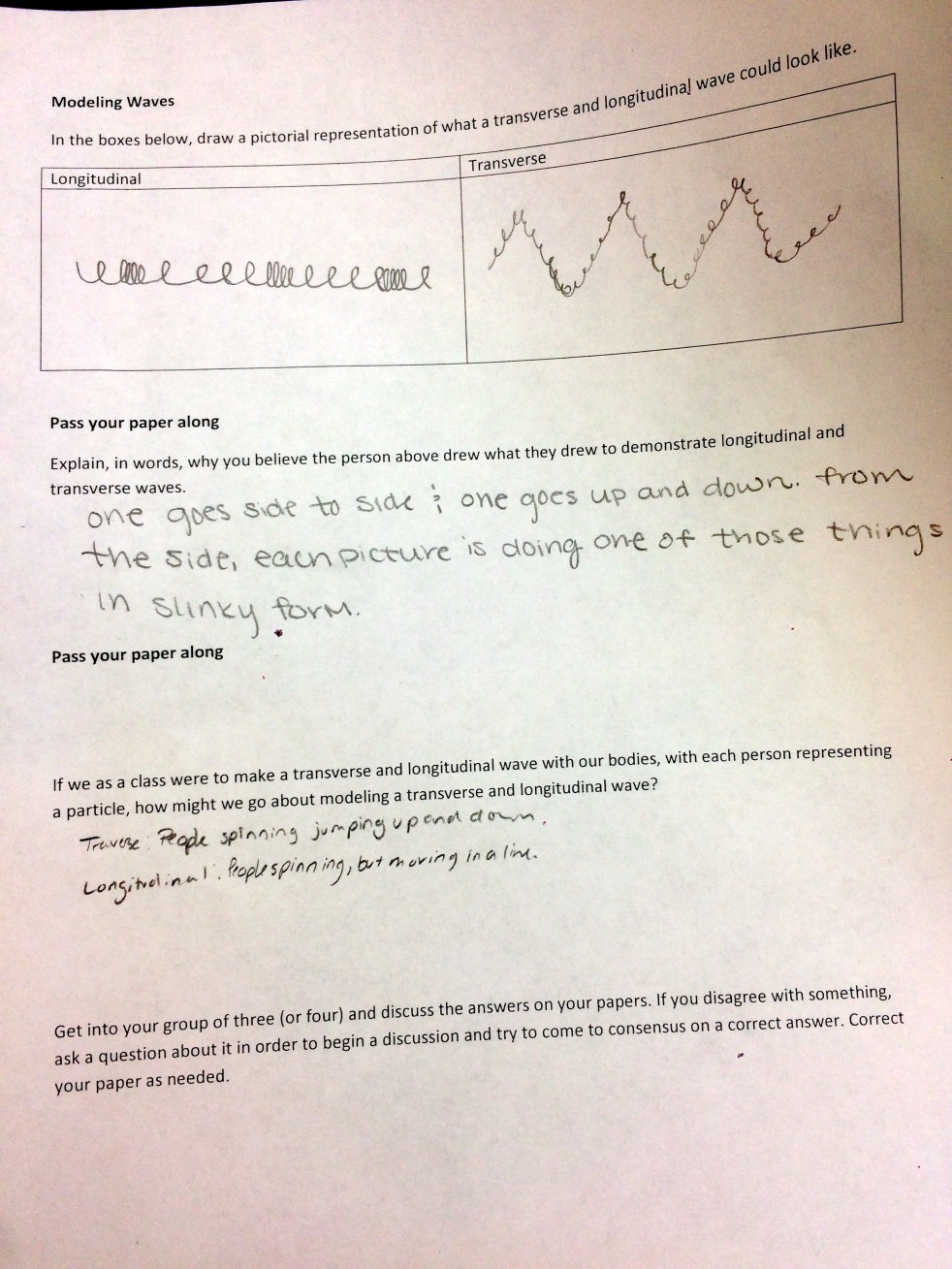

My former adviser, Mats Selen, has been working on a new project:

My former adviser, Mats Selen, has been working on a new project: